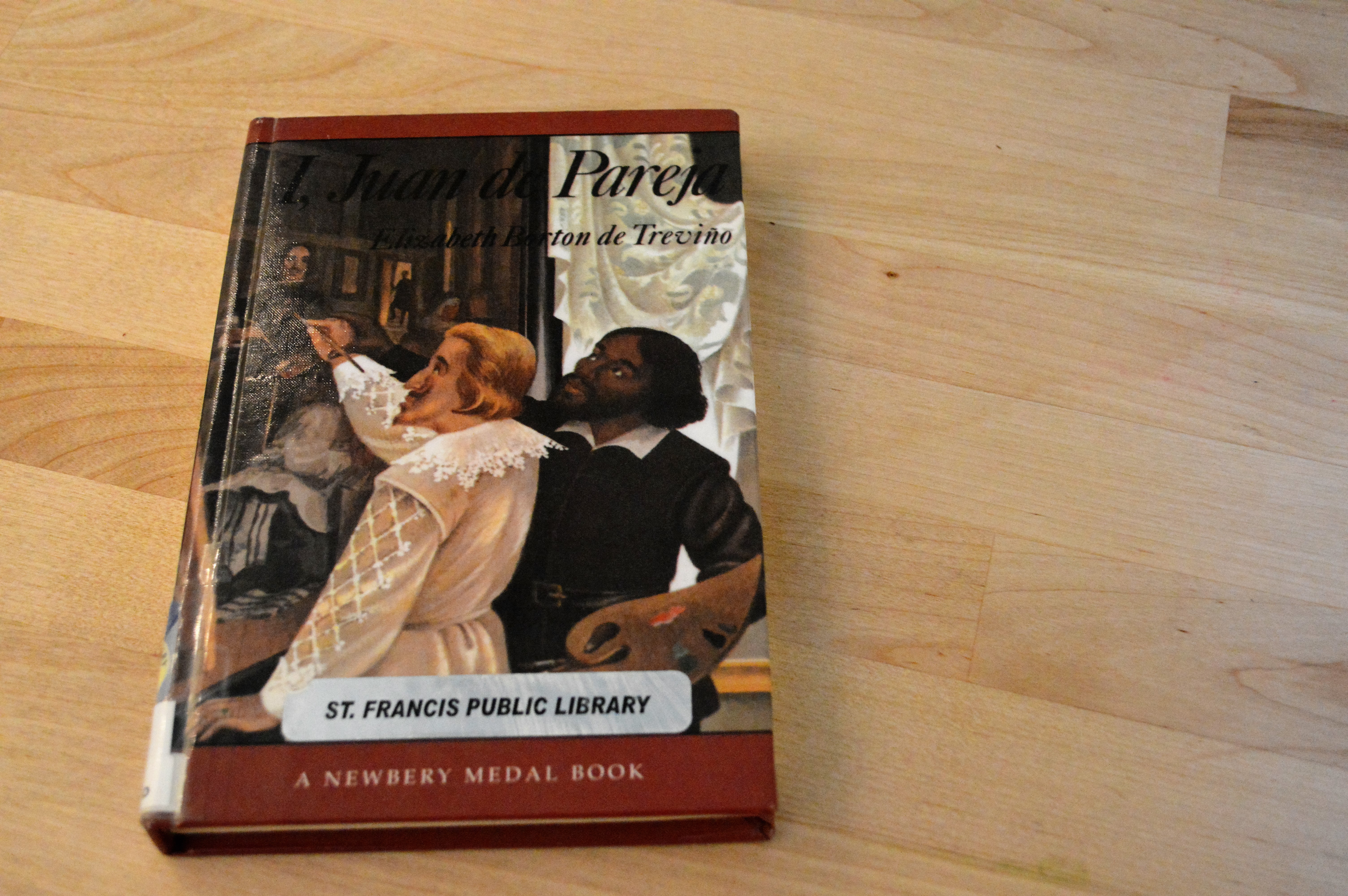

Elizabeth Borton de Treviño’s 1966 Newbery Award Winning book, I, Juan de Pareja, de Treviño creates a beautiful story of the real life slave of seventeenth-century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez. Using the few written records available (those relating to Velázquez inheriting the young slave from relatives and giving the old slave his freedom) and a wealth of dated paintings, de Treviño fleshes out the life behind Velázquez’s painting of Juan de Pareja, giving de Pareja a unique and compelling voice, strong relationships, and a vibrant setting.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Juan de Pareja, c. 1650

What I liked. I really liked the details of Juan de Paraja’s life: his learning to read, his kind heart, his careful observations, his desire to paint, and his ultimate freedom. The worlds of Seville and Madrid, Spain and Italy in the 17th century really were some of the best parts of the story.

What was interesting. I think that making the horrors of something like slavery or the Holocaust come alive for students is a real challenge. Sometimes numbers and generalizations of conditions don’t make the same kind of impression that a personal narrative or small anecdote do. I remember helping my husband Evan plan a lesson on the Atlantic Slave Trade and coming across a story of a ship running into a school of fish, its crew netting hundreds of fish, gorging themselves on them and then throwing the abundant remains overboard without giving any to the starving slaves in the hold, and that small terrible story brought a real reaction of anger and indignation out of the students, much more so than the data about millions coming over in the Middle Passage. And I think that the small and terrible injustice of it being illegal for Juan de Pareja to learn to paint when he was so much better than the apprentices that were in his master’s studio is another example of how a personal anecdote of injustice can be such a powerful tool for eliciting compassion and teaching readers about the inhumanity of slavery.

Diego Velázquez, Self Portrait, c. 1650

What were some limitations. I sort of wonder if having a very cruel gypsy who beat Juan de Pareja was a little bit of a stereotype of gypsies and a convenient way to demonstrate the cruelties of slavery while keeping the actual master of Juan de Pareja a remarkably good character. But I’m sure that some slaves, whether by gypsies or not, were beaten and starved as little Juan de Pareja was on his journey from Seville, so it was perhaps a way to keep the story authentic but still not too heavy for young readers.

Diego Velázquez, Self-Portrait from Las Meninas, c. 1656

Similarity to other Newbery winners. This book most resembles Amos Fortune Free Man which is also based on the facts of a real-life, accomplished African slave-artisan who eventually gains his freedom, marries, and leaves a few important records behind. Amos and Juan have similar stories in terms of a mistress teaching them to read (Which I might guess is more an influence of Frederick Douglass’ memoir) and both having remarkably patient attitudes toward slavery. I wonder if a book written today would take such a long-suffering and trusting tone towards slave masters. De Treviño was writing in 1966 and Elizabeth Yates wrote Amos Fortune in 1951, and I think that perhaps the seeds of the Civil Rights Era can be seen in the voice of the 1966 character of Juan de Pareja’s love interest in her anger at enslavement and refusal to wed Juan if she wasn’t a free woman able to bear children into freedom. That sort of passionate anti-slavery rhetoric was also present in the 1962 Newbery The Bronze Bow (although that was about Jewish subservience to Roman Occupation). For sure, Amos Fortune and Rifles for Watie (1957) paint slavery in a distinctly negative light, but there seems to be a new anger present in the 1960s.

In terms of setting, this is the second book in a row set in Spain (Shadow of a Bull). In terms of time, it’s the third 18th century set Newbery (Witch of Blackbird Pond is set in 1687 New England and Dark Frigate is set in 17th century London.) It’s the seventh historical-fiction biography-winning Newbery (Others include Invincible Louisa, Amos Fortune, Carry on Mr. Bowditch, Daniel Boone, Caddie Woodlawn, King of the Wind, Island of the Blue Dolphins). And it’s the fourth Newbery with first person narration (Island of the Blue Dolphins, It’s Like this Cat, …And Now Miguel, and Onion John).

What it teaches me as a writer. I tend to want to shy away from writing injustice for my characters, but we all experience injustice, whether simply being misunderstood or being part of large, systemic injustice. Fiction helps us face our own injustices with courage and perspective, with an ability to know that everyone faces it to some extent, and that real justice is something we all need to strive for not only for ourselves but for our neighbors. And it should be something that I keep working into to my own fiction writing.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, c. 1656

Have you read I, Juan de Pareja ? What are your favorite books that deal with injustice, slavery, and perseverance?

*Note* This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which means if you were to buy a book, I’d get a tiny commission at no cost to you. Thanks for supporting Stories & Thyme!*