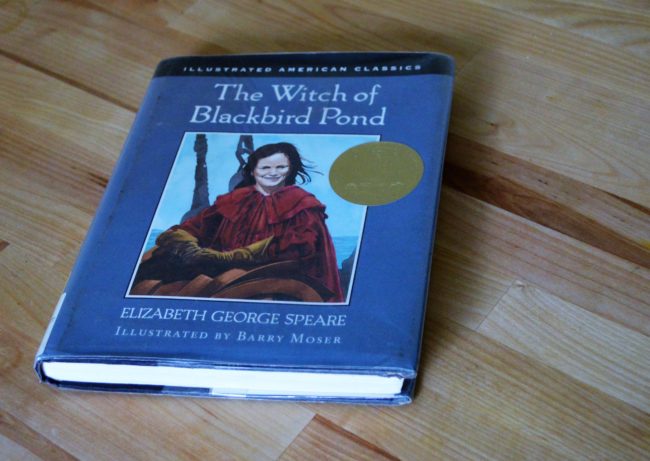

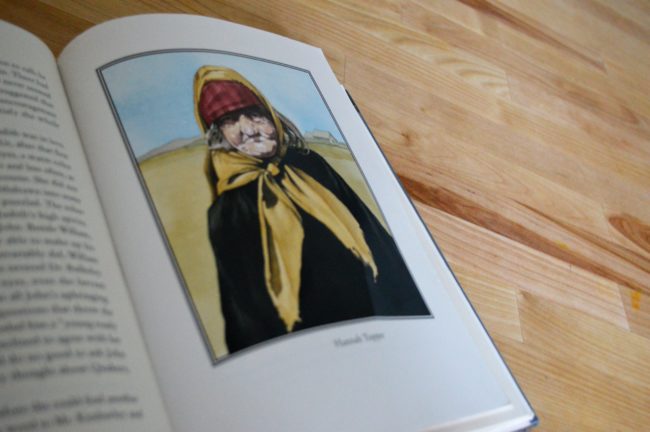

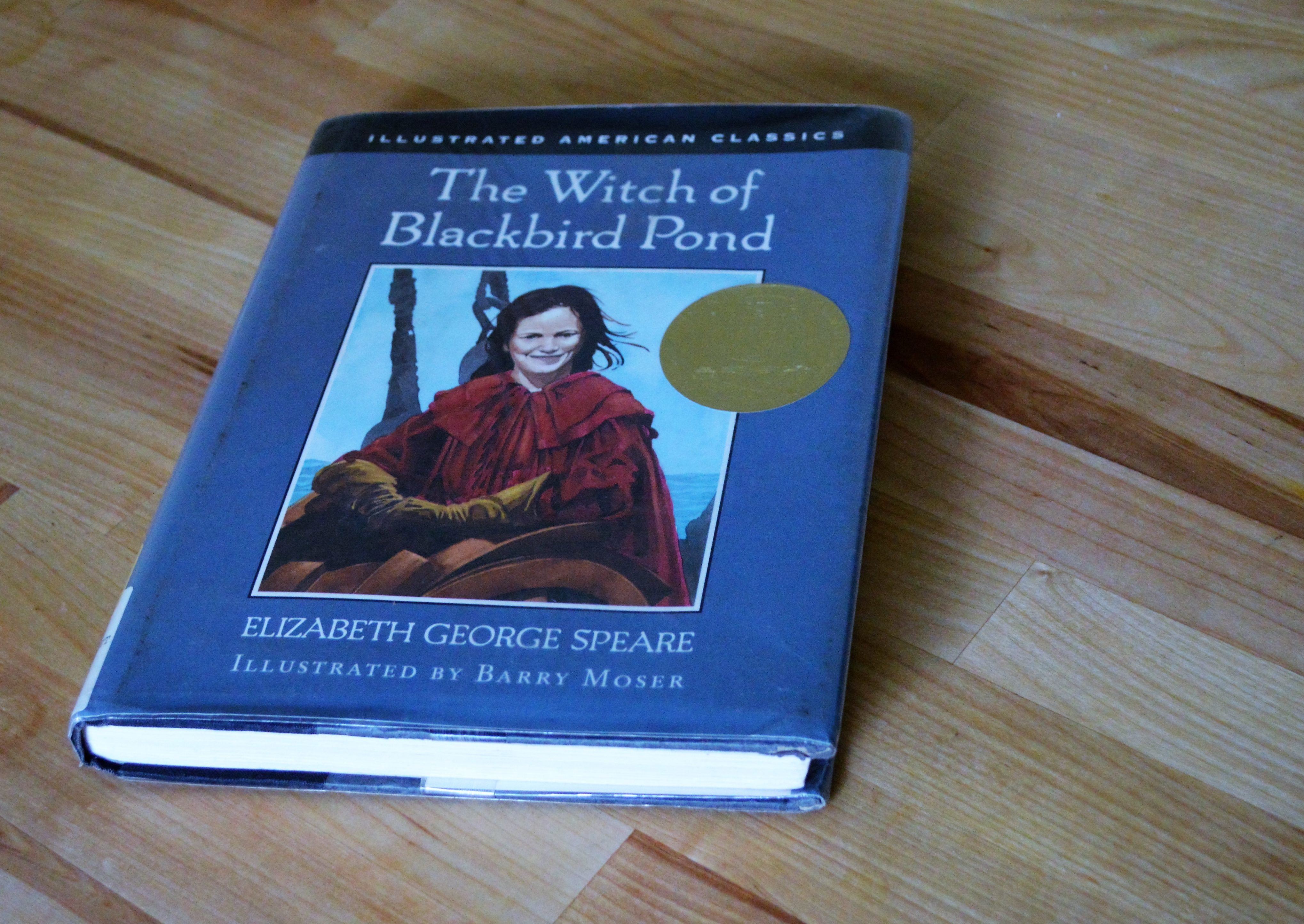

Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond is the first Newbery I’ve gotten to re-read for this Newbery Project that I had been first assigned to read for school. I remember being apprehensive at age 12 that it was going to be about a witch, then really liking the first few chapters, and then being apprehensive that something terrible was going to happen to that “witch.” This book was my first exposure to the early modern New England Puritan witch hunts. Before that, the word “witch” was firmly in fairy tales and Disney movies – a 100% bad guy, or eh, bad-lady in this case. Now it’s hard to imagine that flat portrayal of witches, not only because I’ve read the Crucible and seen other plays about the danger of witch hunts, but because from George MacDonald’s wise women to Harry Potter, magical women in literature are not just portrayed as wicked witches. Hannah Tupper in The Witch of Blackbird Pond is a Quaker whom the Puritans of 1687 Wethersfield, Connecticut are deeply suspicious of and accuse her (wrongfully) of witchcraft, but she, of course, is one of the most kind and godly characters in the book.

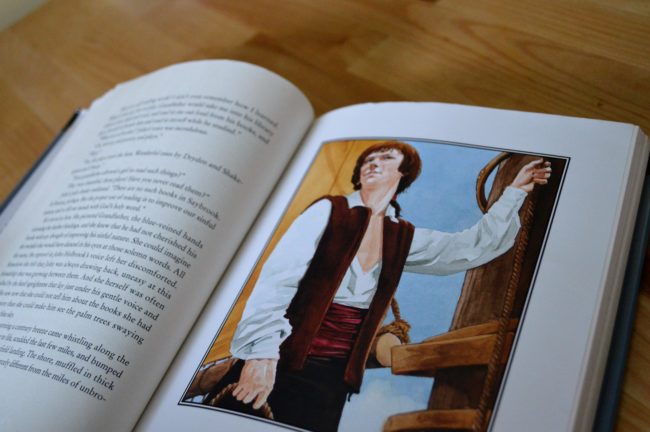

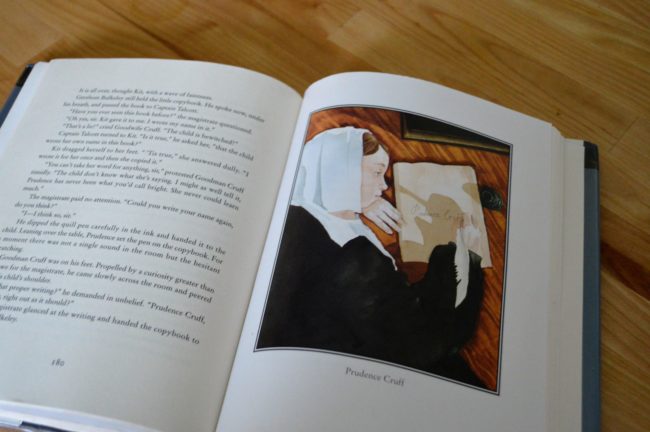

What I liked. My favorite parts of the book were the cozy warmth and wisdom of Hannah and her cottage. Hannah seemed to brim with love and confidence, much like some of my own adopted grandparents. I loved that our main character, Kit, felt so at home there, and it was there that we saw little girl Prudence come into her own, and the sailor Nate befriend and fall in love with Kit. Overall I also thought the three romances of the book were fun to see everyone first with the wrong person, and then feel so satisfied that people sorted out who should be with who at the end. It seems like the first Newbery in which we have a female protagonist getting married at the end of the book.

What was interesting. I thought the portrayal of the dame school and the horn books was the most interesting. In graduate school I spent a lot of time learning about the equivalent of elementary schools in sixteenth and seventh century England— horn books, primers, catechisms, Sunday schools, grammar schools — so I was really blown away with this pretty accurate description of a New England Dame School where the children were learning basic letters, prayers, and reading. I had no memory of that part of the book, and it’s funny that 12 years later I would be doing graduate work on those same schools. Overall, that depiction of schools and seventeenth-century New England life speaks a lot to Speare’s research for the book. (With perhaps the exception that I’m not sure if Puritans were really that into Anne Bradstreet’s poetry at the time, but I hope that they were!)

Similarity to other Newbery winners. There haven’t been too many 17th century books on the Newbery Award list except The Dark Frigate, which also features a ship and a lone teenage protagonist, but the tones and styles (and reading levels) of those two books are pretty different. We’ve had a couple of 19th century New England girls feature in Newberies like, Invincible Louisa or the first chapters of Hitty her first Hundred Years, or 18th century New England boys with Johnny Tremain, The Matchlock Gun and Carry on Mr. Bowditch. In style, Kit’s story feels more similar to Caddie Woodlawn or Roller Skates, but really it seems to be ushering in a new era of strong outsider female leads, a theme that we’ll come back to in coming Newberies.

What were some limitations and what it teaches me as a writer.

One essential ingredient in novels is the tension. Without tension in the form of obstacles to the goal, or problems to be overcome, you don’t really have a story and you likely won’t keep a reader’s interest. It’s a bit like keeping tension on a fishing pole: the fish bites the lure attached to your line, gets hooked in the mouth, and then you reeling in the lure and the fish pulling keeps tension on the line. Not enough tension on the line, and the fish can get free from the lure. But too much tension on the line, and the line can break or the lure can get ripped out of the fish’s mouth (that’s a little gruesome I know, but the fish is about to die and be cut up so…). Too much tension in a story can make a reader squirm and wriggle free as well.

I have come to term this as “dread.” A good amount of tension is thrilling and exciting: it keeps you wondering what will happen next, and flipping pages. For me, when tension turns to dread, I want to hide my eyes and either scan the awkward passages, or put the book down.

I think that the point when tension turns to dread is different for every reader, just like some people love horror movies and haunted houses, but for me that’s way too much dread. Dread doesn’t necessarily have a direct relationship to the height of the stakes. For example, the world may implode in a fiery furnace and everyone might die if the protagonists don’t succeed and that’s nothing but thrilling, or the stakes might be a difficult family relationship. But if there is no perceivable way out, no understanding of why the protagonist is acting in such a way that is clearly causing him or her pain, then that can be something I dread reading.

The Witch of Blackbird Pond helped me articulate this difference between enough tension and dread. Most of the time, Blackbird had just enough tension, but occasionally in the middle of the book I started to get seriously worried about Hannah Tupper. Now this is probably a little due to the fact that I had read the book before, so I knew something was coming, and my outside knowledge that witches were often burned. But mostly I think it’s because of the narration and foreshadowing—we knew that something bad was coming and we knew that Kit was pretty much just not paying attention to the signs. When Kit was in jail I wasn’t worried about her dying because she’s the protagonist, and they almost always survive, and she was thinking about her options, planning in her mind her next move, letting us think with her the scope of the problem and its outcomes. But when Hannah was in danger because Kit was getting careless about seeing her, Hannah seemed very much in jeopardy.

One of my biggest issues with …And Now Miguel (a few Newberies ago) was that I just could not understand why Miguel was constantly having painful miscommunication with his father. I knew that Miguel wasn’t going to die, but I just could not connect with his reasoning or logic behind what he did. In the end I really enjoyed Blackbird, and the tension over Hannah made the relief at her escape much greater. But if I hadn’t been reading the book for the project, I might have put it down. I think the art of tension is tricky, important, and will make some people love a book and some people feel too anxious in reading it to finish it.

Have you read The Witch of Blackbird Pond? What are your favorite books that have just the right amount of tension? Do you think there is such a thing as too much tension in a book?

*Note* This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which means if you were to buy a book, I’d get a tiny commission at no cost to you. Thanks for supporting Stories & Thyme!*

Amy,

I really like your point about “dread.” If there is too much dread in a story I will stop reading, watching, or listening. If there is no tension I will be bored. Just the right amount of tension is needed! There is the art of the thing! I’m looking forward to reading your book and seeing how you are going to try to incorporate all the lessons you are learning. Grandpa Doug

Thanks Doug! I know I need to work on increasing the tension in my stories, so I doubt that there will be much dread! But I am constantly working on adding more tension and obstacles in. I’m reminded of one of my favorite passages from Donald Miller’s book A Million Miles in a Thousand Years where he talks about working on his novel as he walked to his office “I’d create my stories while I walked, thinking about what I wanted my characters to do, what I wanted them to say, and how I wanted them to throw headlong into whatever scene was coming next. I felt like God when I walked, always making worlds, and I believed when I arrived at my building and climbed the stairs and went into my office and shut the door, I would sit down and bring these worlds to life. But it never happened. I was a half-hour walk, so by the time I got to my desk, I’d had plenty of time to plan whatever was coming in the book. But stories are only partly told by writers. They are also told by the characters themselves. Any writer will tell you characters do what they want. If I wanted my character to advance the plot by confrontation another character, the character wouldn’t necessarily obey me. I’d put my fingers on the keyboard, but my character who was supposed to go to Kansas, would end up in Mexico, sitting on a beach drinking a margarita. I’d delete whatever dumb thing the character did and start over, only to have him grab the pen again and start talking non-sense to some girl” (p. 85)…Miller goes on to talk about how he, as the main character of his life, needs to start doing more adventurous things, how he’s own life lacked tension and plot and big goals that characters in stories have. But I always think about his characters ending up on a beach when I think about how I need to get my characters into conflicts and obstacles.