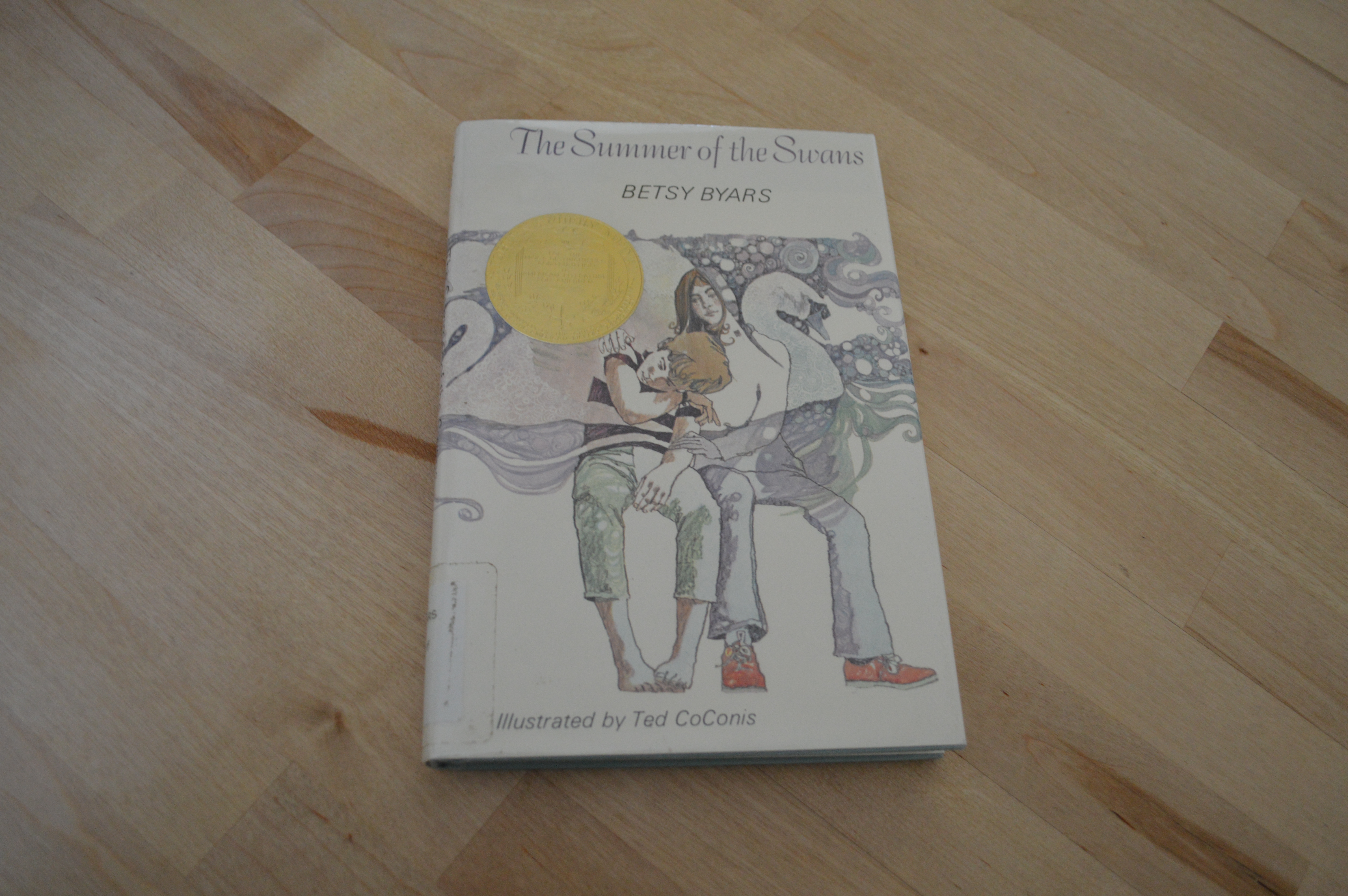

The 50th Newbery Award went to Betsy Byars’s coming of age tale, The Summer of the Swans. The story follows 14-year-old Sara Godfrey who is deep in the middle of some quality teen angst (Are her shoes too big? The wrong color? Why does everything make her mad, and sad, and blah?) over the course of a few days when her disabled younger brother Charlie goes missing after he wants to go back to see the swans who’ve landed in the town’s lake. In the search for Charlie, Sara discovers a bit about herself and her community.

What I liked. I have to admit that reading teen angst feels almost as bad as reliving it, which is the point. (Like much of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, or the second quarter of Deathly Hallows) It’s supposed to be cathartic and jarring, allowing you to enter with the character into the dark period, in order to emerge cleansed and renewed. (In the white/alba section if you want to talk about the alchemical phases!) So while reading about Sara’s shoe problems and her short temper with her older sister Wanda, Aunt Tille, or brother Charlie weren’t fun, they set the stage for her change of heart so well. (And the book is pretty short, which made it better.) My favorite bits are at the end (SPOILER ALERT) when this boy, Joe Melby, who Sara was absolutely convinced stole her brother’s watch, turns into a budding new friendship between the two as they search for Charlie.

What was interesting. I thought the West Virginia setting was one of the more interesting bits of the book. The Godfrey’s mother has died, and their father is mining in nearby Ohio, coming home for an occasional weekend. The poverty that Sara Godfrey focuses on is more social and relational than financial. But Aunt Tille has only one good dress, and the solution to Sara’s shoe problem is to dye them a new (and turns out terrible) color, so it seems they are not swimming in money. The hilly terrain of West Virginia with its woods and gorges plays a big part in Charlie’s getting lost and the difficulty in finding him. Sara’s character doesn’t seem too impressed or interested in the uniqueness of her setting, but it is something that the reader notices as one of the many things that make Sara’s life rich and worth appreciating (which she does, after she’s gotten over herself, a bit).

What were some limitations. I don’t know if any book that has a significant amount of accurately rendered teen angst is going to be one I want to return to over and over again, but the further away from the book I get, the more I find myself recommending it! A Wrinkle in Time starts out with a good few pages of Meg Murray having some teen angst, but for some reason it’s less annoying and more relate-able (also much shorter). I think that The Summer of the Swans has a bit more of a limited third person narrative point of view, keeping us closer to the thoughts of Sara or Charlie, while A Wrinkle in Time has a third person narrative point of view that is just slightly more omniscient, letting us see a bit more of the scene than just what Meg is taking in.

Similarity to other Newbery winners. In addition to Wrinkle in Time, this book also reminded me of a number of coming of age Newbery winners: It’s Like This Cat, Johnny Tremain, …And Now Miguel, The Bronze Bow, and Up A Road Slowly all of which have teen main characters who go through quite a bit of mood swings and agitation as part of their maturing and coming into young adulthood.

What it teaches me as a writer. Normally in this section, I like to think about craft more than content. But this book’s most lasting impact on my own writing was that it spurred me to do some research about swans. I have a swan in my own novel (his name is Salix and he’s a little grumpy). So I was excited to see how these swans were written. But what caught my attention most was that they were called “mute swans.” This gave me significant pause because so far I have written my swan as a rather noisy bird, hissing and honking and generally communicating his displeasure. Now I know that I’m writing a fantasy book, and Salix may or may not be a bit magic (you’ll have to read it to find out!) so of course I could choose have my swan make noise, but I like those choices to be deliberate (and so that I could at least acknowledge that I knew swans don’t normally make noise.) I had to leave the pages of The Summer of the Swans to learn about Mute Swans and swan noises. So here’s the scoop from Wikipedia: Mute Swans do make some noise, usually in communicating with their young, but compared to other swans (Whooper or Bewick Swans in Europe, and Trumpeter, Tundra, or Whistling Swans in North America) they are fairly quiet.

I think that fantasy writing is quirky that way, you get to make things up of course, but that doesn’t totally leave the reader willing to overlook factual errors. I found the pumpkin in Newbery book Trumpeter of Krakow distracting because pumpkins are a new world crop, and the book takes place in the mid-1400s before any Europeans had seen a pumpkin. And all it would have taken is for the author to say something like it was a gourd almost as large as today’s pumpkins to acknowledge they were making a deliberate choose. So while I’m sure that I’ll make my own pumpkin-mistakes, The Summer of Swans, helped me think about what type of swan and the noises he could make and how I should explain them.

Have you read The Summer of the Swans? What are your favorite coming of age/teen angst books ?

*Note* This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which means if you were to buy a book, I’d get a tiny commission at no cost to you. Thanks for supporting Stories & Thyme!*