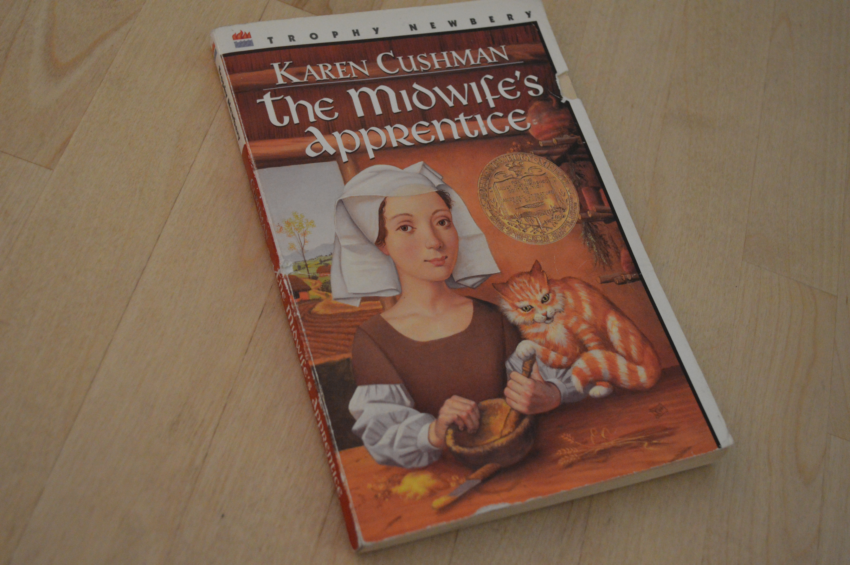

1996 Newbery winner, The Midwife’s Apprentice, by Karen Cushman has long been a favorite of mine by one of my long-time favorite authors. I think that reading Karen Cushman’s first novel Catherine Called Birdy (1994) was one of the reasons I wanted to study early modern English history in college and graduate school. I love everything that I have read by Cushman, especially her medieval young women: Catherine, Matilda, Meggy, and of course our young midwife’s apprentice Alyce–formally called Brat or Dung Beetle.

What I liked. I love how Cushman has the ability to put her characters in truly horrible historical conditions, with believable flaws and rough edges, and to somehow create a home for them and some warmth to soften them. In this book, we open with an unnamed young girl staying warm in a dung pile earning the moniker Dung Beetle from a local gang of boys. The dung pile belongs to the village midwife, who, needing an assistant, refers to the girl only as Brat. And after a few months of working with the no-nonsense midwife, our young apprentice goes to a fair to buy some supplies and comes back with a name she likes: Alyce. Alyce is tough and worldly wise, but compassionate and uneducated. She rescues a cat, a boy from drowning, and helps a poor woman birth when the midwife has to go attend the rich manor wife’s labor. Alyce exacts clever revenge on her tormenters by preying on their fear of the dark and the devil.

Just like all of Karen Cushman’s books, The Midwife’s Apprentice is historically well-researched. While I’m sure there are some historians who specialize in midwifery texts and histories that could point out flaws, I didn’t see any. I think that Cushman does such a great job making the heart of the story about the characters, but keeping the historical context pretty grounded in her research. One fun little thing I did notice was that she has Alyce give the midwife Jane the last name Sharp because she’s a sharp woman. In real life, Jane Sharp was the author of a famous midwifery text. (Below towards the bottom of the image you can see it say “By Mrs Jane Sharp practitioner of the art of MIDWIFRY above thirty years”)

What was interesting / What it teaches me as a writer. Reading this book again as someone who has spent a great deal of time studying early modern English women and children, and who has gone through two natural births of my own, definitely means a different perspective than when I read the book for the first time at age 12. I was kind of horrified by some of the yelling and slapping and general meanness to the women in birth by the midwife. Also, I’m sure this happened, but I don’t understand the general trope in nearly all books or movies (set in nearly all eras) of men running to the midwife’s house all worked up about how their wife needs help right then. Does no one send someone to the midwife not in a panic? I know people do arrive at the hospital with moments to spare, (I overheard someone at the hospital when I gave birth get there only a few minutes before delivering, while I was slowly laboring quietly in my room). I might be biased because I’ve had two slow labors, but I really don’t think the majority of people are in that much of a panic before a birth!

Also, some of the ingredients that the midwife uses are things I recognize that midwives still occasionally encourage their patients to take for a gentle start to labor before more intensive medical intervention are used. (Like fennel for nursing mothers.) But most of the wonderful lists of plants and remedies I didn’t recognize, and a few I’d never heard of, and since I’m more educated on birthing herbs than your average 12 year old reader, it’s obvious to me that Cushman didn’t expect any of her readers to recognize the herbs. Still, those short lists of mysterious sounding midwife herbal tools add so much texture and authenticity to the story: “ragwort and columbine to speed the births, cobwebs for stanching blood, byony and woolly nightshade to cleanse and comfort the mother, goat’s beard to bring forth her milk and sage tea for too much, jasper stone against misfortune, and mistletoe and elder leaves against witches” (page 13). I would think that readers wouldn’t be able to handle such longs lists, but I think Cushman really uses them to her advantage and makes them an enjoyable part of the book, even though reading a list of everything a midwife uses all at once would be confusing and not fun. I find it so interesting to try and guess what will keep a reader’s attention if done one way, but wouldn’t keep the same reader’s attention in another way.

What were some limitations. I’m probably biased because these books have such a special place in my heart, but I can’t think of anything much in terms of limitations. I think there are some authors who would explore the darker and rawer side of children who have been so poorly mistreated and neglected as Alyce (Kimberly Brubaker Bradley comes to mind as someone who does this well, but in a way that’s still readable for middle grade novels) and Midwife Jane Sharp is not as kind or loving as I’d want my main character to end up with for a happy ending, but everything works so well in this story, that I don’t think I’d actually want her to change anything. I think there are styles of writing that create a consistent world and other authors would have a different take and explore the depth of despair or the heights of affection and home more, but within this story Cushman’s choices work well and keep a consistent tone and world.

Similarity to other Newbery winners. It reminded me of The Whipping Boy the most in terms of medieval setting and tone, but there are some other lovely medieval or early modern Newbery books like Adam of the Road, Door in the Wall, Witch of Black Bird Pond. (And it’s considerably more enjoyable to read than some very early medieval-set Newberies like The Dark Frigate or Trumpeter of Krakow which lacked the warm relationships and humor of my favorites.)

Have you read The Midwife’s Apprentice? What are your favorite medieval historical novels?

*Note* This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which means if you were to buy a book, I’d get a tiny commission at no cost to you. Thanks for supporting Stories & Thyme!*