With Call it Courage by Armstrong Sperry, the 1941 Newbery winner (number 20), we join Mafatu, a boy afraid of the sea, as he leaves his island in a moment of rash courage and survives a wild storm. He lands on a wild island where he must survive and escape being made a human sacrifice on the sacred alter of the cannibals who use the island for that purpose.

What I liked. As a retold Polynesian myth, I loved spotting the traditional hero-cycle parts of the book. The boy leaves his world, almost doesn’t make it into the new world, faces a series of challenges, gains skills and triumphs, before the climactic final conflict and return to his own world with his treasures.

What was interesting. I was fascinated that again, like last week’s Daniel Boone, we have in the middle of WWII, a Newbery with Native peoples as enemies—this one with cannibal-human-sacrificing-idol-worshiping-ones no less. When Mafatu is crouching, watching those scary men and their giant carved black stone faces, it seems very Indiana Jones, like the Nazis should be there as well trying to gain some sort of weird occult power.

What were some limitations. Well the paired-down nature of this survivor story probably contributed to its being a bit exoticized. It also lacked relationships. The genre of a Robinson Crusoe/Survivor story can be a difficult one in which to have relationship growth, but relationship growth is one of the things that May B by Caroline Starr Rose does so well. Even though May is alone for most of the book, we grow to understand her family as she thinks back to the years that led to her time on the prairie. I love that book.

Why I think it’s a Newbery. Call it Courage is a solid hero/coming of age story in an exotic setting which is an early Newbery favorite.

Similarity to other Newbery winners. The seafarers journey is a theme shared by some of the first Newberies: Dr. Dolittle and Dark Frigate. The misunderstood boy who comes into his own is a bit like Dobry. But it probably is most like some of the short myths in Tales from the Silver Lands or Shen of the Sea, but I liked Call it Courage a lot more than those two.

What it teaches me as a writer. Since the story was such a straightforward set of new obstacles for Mafatu to face, it was a really great book to think about the hero’s journey. Even though I had a sense of what was going to come, it was still satisfying to read as Mafatu kills the boar, and then the shark, and then the octopus, saves his dog, builds a ship, and conquers his fear of the sea. It’s a good reminder to build in those escalating challenges into my own book.

Have you read Call it Courage? What are your favorite survivor or desert island books?

*Note* This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which means if you were to buy a book, I’d get a tiny commission at no cost to you. Thanks for supporting Stories & Thyme!*

You are such a sweetheart. Thank you.

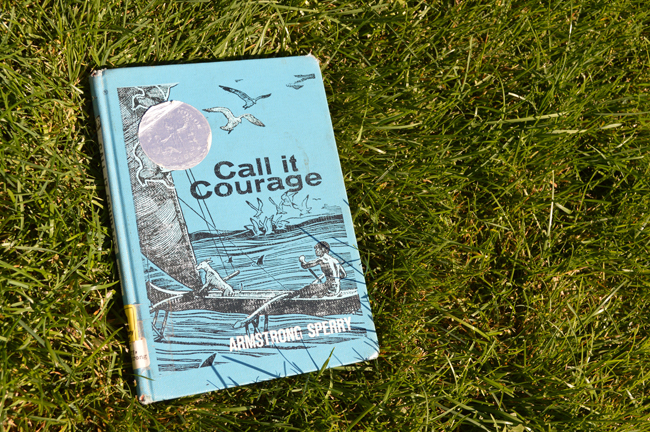

This book left an indelible mark on my spirit—in the best way possible. You’ve mentioned nothing in your writing about the woodcuts, which are so much more evocative, and in some instances frightening, than a simple illustration would be—particularly the images of Mafatu in his canoe alone in the sea with his animal companions. I do appreciate that you’ve included photos of these in your piece, because they are central to the experience of the story—lovely, terrifying, beautiful, and maybe even transcendent, when viewed by a young reader with the necessary sensitivities—and I must’ve been such a reader, because I returned to this book again and again after I discovered it, probably when I was about 8 years old. The woodcuts convey, more powerfully than words, the monumental nature of Mafatu’s quest. Also—“natives as enemies”—Mafatu himself is a “native,” so his encounter with other Polynesian tribes that happen to be cannibalistic is in no way “othering,” although I grant that the entire story exoticizes the Polynesians in a way about which I’m sure people are now using the word “problematic”—and yet, if they are, they are doing so mistakenly, and without regard for context. We know that some Native American tribes, for example, made enemies of other tribes, and waged war against them, before they had a common enemy in the European colonizers.

The story is on one level a conventional adventure story, but the heart of the story is about conquering one’s fears—and through Sperry’s poetically spare and direct prose, as well as his woodcuts, Mafatu’s fears become our own, and we experience them as viscerally as he does. I am sure the story might resonate with girls as well as boys; however, the story does directly address the cultural expectations bound up with masculinity, and that aspect of the story was directly relatable to my own insecurities about not being “enough of a boy” at the age when I read it. As Mafatu comes of age in his village, terrified of the sea unlike all the other boys his age, and consigned therefore to stay on shore and make nets—“women’s work” in the story……The boy who I was when I encountered the story, who’s grandmother taught him to crochet at a very early age, and who had trouble caring about the activities boys were expected to care about—that boy found that this story spoke directly and poignantly to his particular situation, and I suspect that it may speak to a great many boys, even today—particularly that boy who finds his nose in a book more often than he engages in other kinds of activities people still expect boys to be interested in.

Perhaps it’s dated now, but I would place this book on a short list of books that profoundly influenced my life—in part because the story is told with such immediacy, but also because of those still beautiful, startling images that seared my young consciousness with their beauty and terror. They provided perhaps my first transcendent, aesthetic experience, and they did so while speaking directly to the unspoken, terrible fears I experienced as that boy who didn’t quite fit in with the other boys—and it gave me hope that I too might prove everyone wrong, despite the monumental difficulty it would require to face my fears.

This experience of the book might perhaps be reserved for young readers—but I wanted to share it so that you might understand why this book so richly deserves that medal.

Thanks for sharing how much this book meant to you Joseph! Isn’t amazing how the words and images stay with us for our whole lives! I’m so glad that it came into your hands at just the right time.